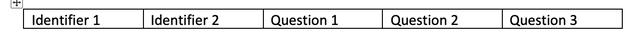

Today, I will tackle how to teach undergraduate researchers the skill of keeping track of the papers they have read. I call what I teach a “citation table.” Citation tables, as a skill, were taught to me by my master’s advisor, Dr. Corinne Wong. There are examples of her using them in her papers (Wong and Breecker, 2015; Wong et al., 2015) and you might recognize the concept. The idea is to basically create a summary table that helps you keep track of what you have found from each paper within a set of papers. In her work, Dr. Wong often published citation tables to summarize the recent work done about a subject. When I teach citation tables to undergraduates, I like to teach them as a flexible tool that can help students keep track of what they are reading. Additionally, they can help students stay focused on their goals – if they are reading a set of papers to understand how Mg/Ca works in the ocean, for instance, then they can keep that in mind as they are reading and not get overwhelmed in other (unnecessary) part of the literature. A good citation table will have space for identifiers, places for students to write down key information from the text, and an answer to a question they have about the field. Here is an example of one that I made for a grant. The goal of this table was to summarize the global advancement on the subject of cave monitoring. I had a few questions in mind, such as: 1. What equipment are researchers using now? and, 2. What physical or chemical changes are researchers interested in monitoring in caves? With that in mind, this is an easy lesson to teach and it is one that can be practiced many times. In the end, it will help students write a literature review or introduction to their project report! Step 1. Talk about questions! Have a group discussion where you, as the leader, model the process of identifying a question (or 3) that is answerable in the existing literature. Examples: I might think (on the more technical side): how do other people interpret this rise in precipitation amount? Or, how have other people dealt with this type of uncertainty? Or, how do other researchers correct for this variability in standards? On the broad side, I might think: How has California precipitation been summarized up to this point? Or, what does the recent literature say about this type of variability in the Santa Barbara Basin? Once I have identified a question like this, or a few, that I need the answer to, I turn to the literature and find 10-15 papers that will help me answer them. Step 2. Start a table! Once you have modeled this process, give the undergraduates time to think about what questions they may have about a process or a method and write them down. Great! Now everyone has 1-3 questions and they can be set loose on the literature (well in just a second). Usually here, I open a word document and start a table that looks like this: The identifiers can be whatever you or the students use to identify papers. When I am taking notes to myself, I like to use the last name of the 1st author and the year. And then, because I work on caves, the second identifier is the cave name. But, depending on the topic or your students’ preferences, it can be WHATEVER will make it easiest for the student to remember what paper they are talking about. In all likelihood, no one but them will ever see this table, although it could get cleaned up and published, as Dr. Wong demonstrated for us. Step 3: Practice in a group setting! Usually here, I ask the students to share 1-2 of the questions they wrote down and I show them how to use Web Of Science or Google scholar to find a paper that may tackle it (here students can practice their previous skill of skimming a paper quickly). Alternatively, if you have come up with questions yourself, you could model this process on your own questions. After we have discussed how to find papers (a skill itself, to be sure) and I am sure the students all have a first paper to start with, I leave the students to begin working with paper #1 to fill out the first row of their citation table (some students may want to work in a separate quite space, definitely allow that). I usually let them have 30 minutes for my own time restricted reasons, but I float around so that I can help students who get stuck. I constantly remind the students that this is a space where they can write in their preferred language or shorthand, using their preferred technologies, etc. It is for them to keep track of their thoughts – they should use things that they themselves will understand later. It's not for me. Step 4: Check in regularly! I find that it works well if you check in with students on their citation tables, regularly. Again, they don’t have to turn anything in – but you can encourage students to keep adding to the table, or to make a new one. Their questions may change, that’s OK, they should just start a new table with their new questions. It’s also OK to have one citation table for methods and one for “broader scope” stuff. Once students get used to doing things like this, it is easier for students to keep track of what’s important to them (at the time) about the paper they are reading. If they eventually evolve past the citation table – then that’s alright too. This is just a starting place but one that could help them down the line when they are turning back to the literature to write (hopefully).

1 Comment

|

AuthorI am a Ph.D. Candidate who actively tries to create an equitable and enriching experience for undergraduate researchers, I post weekly about the things I teach and my experiences with undergraduates. Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed