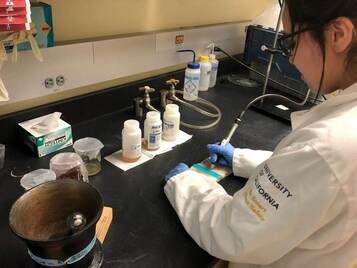

I believe that students should be able to design their own projects. However, undergraduate students will not be prepared (likely) to assess if the size and the scope of the project they are designing is reasonable in their time frame. Additionally, due to funding or expertise, you may want to guide undergraduate students working with you into one type of project or into one field site. Consequently, the student may get freedom in how to design their project, but they may need guidance from you on how to fit it in your overall goals. (Pictured is Liz sampling stalagmite carbonate for her UG thesis) Step 1: Find projects that you will be excited about! I’ve seen this happen many times: advisors “assign” projects or field locations to students (and grad students) that they themselves aren’t really excited about. WHY? To me, this will inevitably lead to subconscious communication from advisor to student that the project isn’t worth doing. The student might easily get overwhelmed because there isn’t any passion guiding their work. AND, you will stop prioritizing it as the advisor because you’re not excited about it. So, help guide students into areas of the work, chemical processes, or locations that you are genuinely curious about. I am not asking for you to give your pet project to an undergrad, and I am not asking you to find a project that requires an NSF proposal to fund, but just something that sparks your interest. Example from my mentoring: I think, usually, about a specific cave (field site). I know that someone (likely me) will need to go to this cave regularly and it will need to be monitored for a variety of chemical/physical changes. For me, I am genuinely curious about how this cave (and all caves) changes seasonally in both a chemical and physical way. Therefore, I try to design undergraduate projects that involve this cave, one of the chemical/physical parameters that is going to be sampled for already, and how it will vary seasonally. Maybe the student is interested in something tangential (to me and my work), like how that will affect the biome of the cave. That’s fine, they can do the work because of what they are interested in, but the data they collect will also be interesting to me and the overall goal of the work. Step 2: Keep it simple. A simple project in my world is ONE physical or chemical change in a cave (mentioned above in the example). If the student has time, they can then choose to look at the same physical/chemical change in another cave and compare them, or measure a stalagmite for indications of the change they are interested in. Keeping it simple is easier said than done – and, more importantly, how do you know if it’s simple? Here are some things to keep in mind when deciding if the project is simple.

If you have a project that can reasonably be completed with a couple of long days in the field or the lab, could be redone if something goes wrong in a reasonable time frame, and that you could help put out fires on, then you likely have a project that an undergraduate student could do. It is important to remember: unlike grad students (in hard sciences), undergrads actually do need to focus on coursework and they are taking a lot of classes. In our dept. undergrads take classes with weekend field trips and 6 hrs of lab requirements - so when will they spend 12 hrs with you in the lab doing column chemistry? Step 3: Convince the students from the beginning to keep it simple. Once a student has chosen their project and has read a few papers on the overall goals of my work (as a whole), I assign them papers that include the kind of data they are thinking they will gather. HOWEVER, this is very important, I stress that they should only pay attention to 1. how the author gathered the data that is like the data they want to collect, and 2. how the author interpreted the data that is like the data they proposed to get. They are instructed, by me, to ignore everything else. This is important, because papers often have many different kinds of datasets, and students could easily become convinced that their work will be meaningless without all of the other data too. If this happens, you have an avalanche of being overwhelmed ahead of you, you do not want this to snowball. There is a different time and place for you to discuss how their project fits into the bigger picture, how it builds up to something like the paper their reading, etc. But keep the focus when your student is just learning about their scale of project – you do not want them to get overwhelmed. Step 4: Compromise or find other advisors. Finally, your student may insist on doing a certain type of project or doing it in a certain location. This is great, it shows passion and drive. I always love to see it. If you come across a student who has specific things in mind, then you should have a discussion about how your work could intersect with their goals. You want to encourage them: do not downplay their goals, call them naïve, or tell them it’s impossible. Instead, think creatively and out of the box about how the student can accomplish what they want to do and also work with you. If you think the project is too ambitious for an undergraduate thesis, you should double check with their timeline. Maybe they intend to stay longer than the traditional four years. Maybe they are willing to work over one or two summers on it. If that’s not the case, then you should have a gentle but realistic conversation with them about scope. You can also suggest a subset of the project that they have in mind to do now to gain skills/experience, and then suggest that they could easily continue that project in grad school. If there is not a compromise on project interests in sight, then ask the student if they would mind if, at the next meeting, you invited a colleague (fellow faculty, fellow grad student, or a grad student from a different lab). In this way, you could find someone who could better advise the project based on the interest of the student, but you aren’t just telling the student “sorry, you can’t work with me.” Together, you, your colleague, and the student can come up with a project that makes everyone happy. Additionally, this could begin a beautiful collaboration, wouldn’t that be nice?

0 Comments

|

AuthorI am a Ph.D. Candidate who actively tries to create an equitable and enriching experience for undergraduate researchers, I post weekly about the things I teach and my experiences with undergraduates. Archives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed